Zumzud, the pilgrim

Gravestone.

January 19, 1799.

BXM 2363

Gravestone of the pilgrim Zumzud (Zϋmrϋd in Turkish, Hellenized as Smaragda) and her husband, the pilgrim Prodromos, with inscription in Greek and the Karamanli dialect (a variety of Turkish written with the Greek alphabet). It is not known how the gravestone entered the Museum. In a black-and-white photograph from the archive, it is depicted on display, possibly at “Villa Ilissia”, accompanied by an explanatory label describing it as a refugee heirloom. Since 2010, the object is on show in the new permanent exhibition.

The names Zumzud and Prodromos are also encountered in a group of dedications, kept at the Benaki Museum, brought by the refugees from the village Kermira in the Caesarea region. According to recent studies, Prodromos and his son Antonios were members of the Tsipeloglou family, who worked as advisors to the local rulers’ powerful family. Their fortune was amassed during the second half of the 18th century through the services they provided to the abovementioned family, but also through banking and trade.

Zumzud and her husband are referred to as “pilgrims”, because they had both travelled to the Holy Land. For many of the subjects of the Ottoman Empire, travelling to the Holy Land signified a religious practice of major importance, irrespective of their faith. Christian and Jews used the honorific Muslim title “Hadji” to describe pilgrims, a term Hellenized as “χατζή” pertaining to those who had visited Jerusalem on a pilgrimage journey.

Taking care of graves: testimonies of refugees

“When it was officially made known that we had to leave, we sent for father Kosmas from Gelveri [present-day Güzelyurt] —our parish priest had passed away a year ago— and attended the last liturgy in our church. We opened the graves of those who had departed this life two, three or five years ago, washed their bones with wine, and reburied them. Then, we set up cauldrons and cooked pilaf, bulgur and meat, and gave it away to the poor for the souls of our loved ones”.

Testimony of Evlampia Moumtzoglou, Athens, Η Έξοδος, Centre for Asia Minor Studies, vol.II, (Athens 1982), p. 30.

“We brought the Metropolitan who prayed at our graves. We wanted to take the bones with us, but in the end, we did not do it. We weren’t all the same. The poor could not afford it. Then, we decided that they should all remain as they were. We prayed. Mourned for them”.

Testimony of Athena Galanopoulou, Athens, Η Έξοδος, Centre for Asia Minor Studies, vol. II, (Athens 1982), p. 115.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

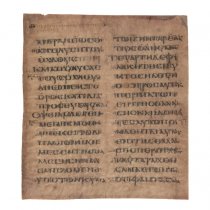

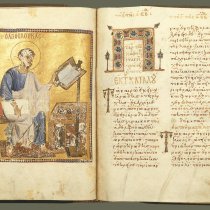

Purple Gospel

Purple Gospel .jpg) The double-sided icon from Tuzla

The double-sided icon from Tuzla .jpg) An emblematic refugee “relic”

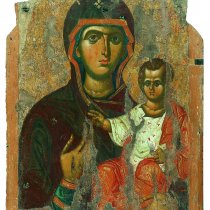

An emblematic refugee “relic”  A byzantine Hodegetria

A byzantine Hodegetria  An Evangelistary from Trebizond

An Evangelistary from Trebizond .jpg) A significant Palaeologan work

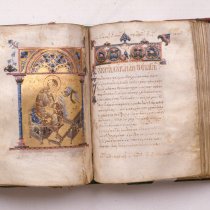

A significant Palaeologan work  Tetraevangelion from Adrianople

Tetraevangelion from Adrianople .jpg) A Cretan icon from Eastern Thrace

A Cretan icon from Eastern Thrace .jpg) “Joined in matrimony”

“Joined in matrimony”  A peculiar neckband

A peculiar neckband  Fragmented memory

Fragmented memory .jpg) Zumzud, the pilgrim

Zumzud, the pilgrim .jpg) A refugee heirloom in “Russian style”

A refugee heirloom in “Russian style” .jpg) An unusual “icon” from Cappadocia

An unusual “icon” from Cappadocia .jpg) "He (the Lord) keeps all their bones …" (Psalm 33: 21)

"He (the Lord) keeps all their bones …" (Psalm 33: 21) .jpg) A Karamanli icon

A Karamanli icon